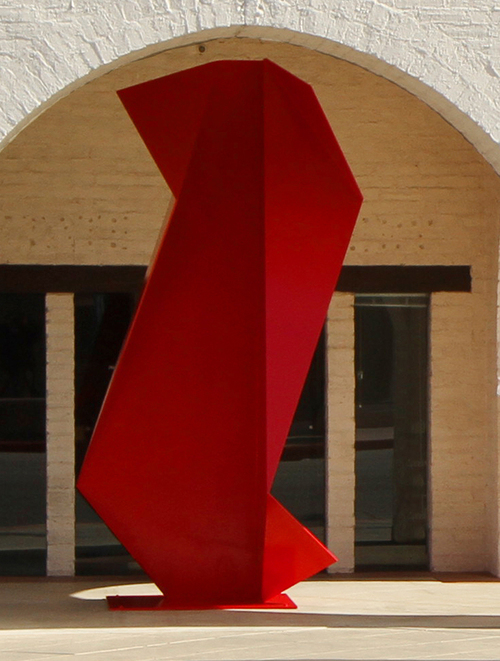

Museums around the world have been home to Betty Gold's steel forms. The geometric pieces are turning up in stylish gardens at houses around Los Angeles.

"I love yellow," sculptor Betty Gold says, and no one entering her Venice kitchen would doubt it. The painted cupboards are a brilliant shade, midway between egg yolk and ballpark mustard — the better perhaps to show off her collection of Spanish and Mexican plates. Born in Texas, Gold is a sun lover, but it's neither home furnishings nor the weather that has elicited her comment. It's a photograph of one of her giant geometric sculptures, works that are in permanent collections of museums as far-flung as Madrid and Seoul.

The sculpture's appearance is deceptive. Although 10 feet tall and constructed from cold rolled steel, its yellow triangles suggest paper creased a moment ago, then halted in the act of unfolding. Indeed, "Sóller II" — named for a town on the Spanish isle of Mallorca, where Gold spends part of each year — almost seems to float among the cream-colored buildings of Pepperdine University's Malibu campus. Its sunny color is brilliant against the greenery and at odds with the piece's monumental size.

Gold's appearance is deceptive as well. It's hard to believe that this willowy, black-haired woman talking so vivaciously about welding turned 70 in February. Her works may be abstract, but making them is a physical business. She still drives a truck and wrangles steel plates onto her studio loading dock. Neighbors offer to help, but "they wouldn't be my neighbors very long" if she called them every time something needed moving. "I've been whacked by my own sculptures," she says with a laugh, holding out a dinged forearm.

In Europe, where Gold's work probably is better known than at home, she is associated with a long-standing movement, named MADI, of artists who deal in bright geometric forms. In the last decade Gold has taken part in major MADI exhibitions in Madrid's Reina Sofía national art museum and in Bratislava, Slovakia, where one of her 10-foot sculptures stands in the garden of the presidential palace. The pieces crowding her studio — many destined for a retrospective of her work at the Esbaluard museum on Mallorca next year — come in primary colors and a variety of unpainted surface treatments. That mottled woodland brown, which looks like a rock after lichen has been scraped away? It comes from dousing the steel with vinegar and letting it sit until the desired patina of rust has formed.

When she uses specially formulated Cor-Ten steel, the surface weathers naturally to an ever-earthier chocolate. (Examples include the 10-foot "Sóller I" at the South Coast Botanic Garden on the Palos Verdes Peninsula, and the 20-foot "Holistic V" by the Harbor Freeway's 9th Street offramp in downtown L.A.) Still, she muses in a Texas accent that's strong despite nearly 30 years in California, "nobody wanted any yellow ones for a long time." That trend seems to be reversing in Los Angeles home gardens. Perhaps it's because yellow works so well with the year-round foliage — and the turquoise swimming pools.

In Beverly Hills, the bright yellow piece that Abner and Roz Goldstine commissioned — all fluid rectangles — stands at the head of a blue-bottomed lap pool, where its reflection appears, more fluid still, in shades of aqua and chartreuse, depending on the time of day. Like so much of Gold's recent work, it's at once purely abstract and then not. Faced with its lifelike motion, a viewer can begin to imagine a life-like creature.

Not all lots are large enough to showcase a 7-foot work and still have room for a perennial or two. But, Gold explains, a monumental piece is only one possible result of a process that begins with lots of folded paper and evolves through 12-inch models constructed from white cardboard and glue. When she is satisfied with a design, she and factory workers in Gardena cut, grind and weld the steel. These maquettes stand two to three feet high, the size Gold generally exhibits in museums and galleries. Larger versions, which sell for upward of $100,000, are made to order.

Varda Ullman and Robert Novick of West L.A. enjoy one of Gold's maquettes from their kitchen window. Their garage takes up one corner of a modest yard, but there's enough room for the small work to serve as a focal point, calm and engaging. The bamboo-shaded retreat, created by L.A. garden designer Katherine Glascock, grew outward, Ullman says, from a kitchen remodel. Gold, a longtime friend of Ullman's, chose soft yellow for cabinets that top the cobalt counter tile. That scheme continues into the backyard, where her triangular yellow sculpture stands at the juncture of a small stand of bearded iris and a patio of broken concrete interplanted with violets.

Wil Kohl, director of the Walter N. Marks Center for the Arts at the College of the Desert in Palm Desert, where Gold had an exhibition last spring, notes that it's unusual to find a woman doing sculptures like Gold's.

"She deals with a major material of the industrial age," he says, "and does it with great dexterity and power."

Glascock, who has designed three gardens containing yellow pieces by Gold, finds the work "remarkable for its absolute simplicity and also its sophistication." The sculptures change hourly as their angles cast a series of sharp shadows. Yet they also stop time, offering a freeze-frame of a flower opening or a bird in flight. For Gold, geometry becomes a kind of alchemy. Straight lines become a curve.

The artist's own garden is a gravel rooftop off a second-floor living room. There are no flowers, not even cactus. Instead the space is planted with some of her earliest terra cotta pieces. Many are figurative; the tallest is the torso of a buxom woman.

Abstract art, especially sculpture, was a largely male arena when Gold was growing up. How did a woman coming of age in the 1950s, a beauty pageant winner who majored in early childhood education, make the leap to apprenticing with Dallas sculptor Octavio Medellin? It wasn't a straight shot.

She married, adopted a daughter and divorced. She met her second husband, a dress manufacturer, while modeling for his line. Their marriage allowed her to go back to school and take courses in art history, painting and sculpture. By the end of the 1960s the cultural climate had become more encouraging to female artists. Gold shared a studio with five other women, and her paintings and a few small sculptures attracted enough attention to win her first show at 35. She began apprenticing with Medellin shortly thereafter.

"It seems like sculpture came so easy to me," she says, sounding as mystified as any master gardener trying to explain a green thumb. "Once I started working with him [Medellin], I remember everybody had to make an almost life-size body piece — terra cotta, hollow on the inside. In the kiln everybody's fell over and broke open except mine. So when we opened the oven, there were about 15 of us standing there, and there stood my sculpture — you know, boobs and bottom," she says, pointing toward the emphatically female torso.

Gold moved to Los Angeles in 1977, on the heels of the manufacture of her first monumental sculpture. She remembers driving to the factory to see it and being "bowled over."

"It was 12 feet tall, but to me it looked 80," she says. "Twelve feet. That's not really very big anymore." The intricate seven-ton fountain, "Redwood Moonrise," that she made for the Ronald Reagan State Office Building in downtown L.A. stands 2 1/2 times as high.

Gold settles back on the sofa. The abstract rug at her feet is one she designed, and photographs on walls are some she has taken on her travels.

"The only sad thing," she says, gesturing toward the TV where a DVD presentation of her work has just finished playing. "I don't have the energy to go back and do all this again." She does have sculptures on her loading dock ready to be picked up for a show in Canada, the Mallorca retrospective to prepare and — when she can find the peace and quiet — more paper to fold.

--